Compact Radial Engines

“When the only tool you have is a hammer – everything looks like a nail.”

Like it or not, life is full of paradoxes.

What often appears perfectly simple can, out of the blue, become much more complicated – unless you’re smart. In an interesting way, a progressive and well-respected machine shop in Western Canada illustrates this point to a “T.” A lot of people tell us Southern Cross Machining is one of the smartest small-parts fabricators in the Vancouver area. Loyal clients rave – and even a few loyal competitors concede – that it’s arguably the most respected job shop in British Columbia. Apparently, the reputation is well earned.

With a sharp eye on quality control, intelligent workflow and efficient machine-utilization, this busy shop consistently turns out exacting, tight tolerance work – on time and to spec. For nearly two decades, an enviable parade of high-end customers has relied on Southern Cross to deliver precision parts, and these very particular purchasers haven’t been disappointed. But surprisingly, in recent years, the most demanding customer has become the shop owner himself.

The name on the building – Southern Cross – is presumably borrowed from the down-under hemisphere’s version of the Big Dipper, the prominent constellation of bright stars near the South Pole. It’s your first hint to the shop’s heritage. But even if you miss the celestial clue, you’ll immediately grasp from owner Leon Massa’s engaging accent that he’s a transplanted Aussie. “Well, you’re dressed up like a dog’s dinner!” he’ll taunt, with a solid handshake and a wry smile.

Next you’ll notice an abundance of sport-aircraft pictures competing for space among the framed awards adorning the wall. That’s your second giveaway. Sharing the same roof with Southern Cross Machining is a separate company christened Compact Radial Engines: a manufacturing venture turning out 2-stroke engines and reduction-drive gearboxes for ultra-light sport aircraft.

As you might guess, Leon Massa’s machining background has deep roots in aviation. He admits to a formative 10-year stretch with Qantas Airlines in Sydney, then a stint at Air Canada, before buying a lathe and setting out on his own. Massa shrugs off the notion that this aeronautical experience makes his shop more obsessed with precision, but his customers might disagree with that assessment. To a large degree, the shop’s stellar reputation stems from its ability and know-how to deliver high-precision parts.

“Qantas never called us machinists,” he remembers, “we were referred to as ‘fitters and turners’. So we not only made the stuff, we also had to put it together.” That interesting aspect of his past – building complete assemblies – has remained a constant in Massa’s business, as have the Qantas-blue coveralls that he and the shop staff (still) wear today. Bolstered by his long extracurricular interest in sport aviation, Compact Radial Engines appears to be a perfectly natural business match for Massa.

“Interesting story there,” he relates. “Down at the local airfield a few years back, I spotted a beautiful little 3-cylinder radial engine, and eventually convinced the guy to tell me where he got it. I really just wanted to buy one for myself. But then, as they used to say in that old shaver commercial, ‘I ended up liking the product so much, I bought the whole bloody company!’”

The company Massa acquired was Italian, and though their small engine designs were spectacular, their market success was not. It was a tough market to crack.

In a world full of internal-combustion engines, the ultra-light aircraft community has traditionally had a hard time finding a power plant it could wholeheartedly embrace. The sport’s demand for reliable high power in an exceedingly lightweight package has driven many engine manufacturers out of business – even in Europe, where the small engine is king.

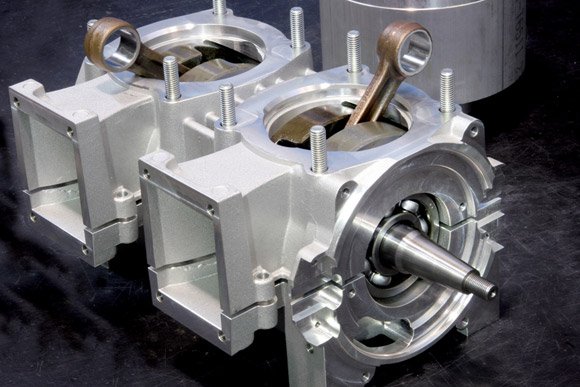

Massa set out to change things, redesigning components to improve the product’s performance and appearance, and moving much of the machining to Canada. Since there are a lot of European fabricators who specialize in small engine parts, Massa buys the pistons, cylinders and crankshafts from these specialty companies. “They’re all our own design,” he stresses, “intended specifically for these engines. They’re not just a generic part off the shelf.” The crankcases, clutches and gearbox reduction drives, however, all are machined at Southern Cross.

The unusual reduction drive is often a necessity for high-rpm 2-cycle engine applications. Rotating a prop too fast will cause its tips to reach supersonic airspeeds that lead to turbulence and destructive vibration. The gearbox is an engineering and manufacturing challenge all its own: In spite of the complexity and high stress loading, its dependability must be unquestionable. “I sell the gearbox to a lot of other companies who adapt it to their engines,” says Massa, “engines that are often much bigger than mine. They’re being tested to 130-horsepower, but I know they can take a lot more.”

Under Massa’s new direction, Compact Radial Engines offered paired engine and reduction drives. These complete units matched the newest ultra-light airframes far better than the heavier, adapted-from-other-use 4-cycle power plants that had become the sport’s affordable staple. Builders of ultra-lights suddenly found they had many more choices to match the machine to the job.

But as Compact Radial Engines became a demanding new customer of Southern Cross Machining, Massa faced some machine-matching challenges of his own. “When I bought the company, I figured it would be a good fit with what we already did,” he continues. “I thought I had all the equipment I needed to make the parts, but actually, I didn’t.

“We couldn’t let the engine company work interfere with the regular job-shop stuff for the established customers. So I decided early on that, whenever I needed parts for my engines, I’d put in a purchase order – just like any other customer.” The devil, it turned out, was in the mix.

Massa has always maintained a wide range of equipment in his 10,000-squarefoot shop, but it was initially stocked with expensive Japanese machines. The demands of the modest, new “just like any other” customer, though, began putting pressure on Southern Cross. The shop’s underpinning of complicated machines required more effort to set up and more attention to run than the medium-price-point engine parts warranted. Things were getting complicated.

Virtually screaming for higher cost-efficiency, the shop’s modest new customer had unwittingly become its most outrageously demanding.

Prior experience, however, was again in Massa’s court. Besides investing heavily in complex, expensive equipment over the years, Massa had also been one of the first in his territory to incorporate simpler and more-affordable Haas Automation machines in his shop. This was back at a time when few Canadian shops had even heard of the new name Haas. Now, to meet the increased demand from the engine company, he bought more.

“I’d had a number of Haas machines over the years,” says Massa, “and I always liked them. I kept my first VF-2 for more than seven years, then sold it to a friend who used it for another three years. I later bought it back from him and used it again for a couple more years before finally trading it up to a bigger one. That machine is still going in a local shop today, doing work just as accurately now as when I first had it here.

“I don’t need to use a complicated Japanese machine that costs three times as much as a Haas, to do what a Haas will do,” says Massa flatly. “It’s not just the cost and complexity of running the high-end machines when the work doesn’t warrant it – it’s the time you waste that makes no sense.”

Haas VF-4SS Super Speed vertical machining centers are used for much of Southern Cross’s 4-axis work. “But,” Massa explains, “they’ve also proved to be a good match for a lot of my engine parts, because they’re quick to set up. I can get on a Haas and get going quickly, then move on to something else.

“Sometimes, I’ll set up one of my engine parts on the end of the table and use the rest of the machine to do other jobs. The crankcase for the 3-cylinder radial is a good example,” he notes. “For most of our engines, the crankcases are machined from Almag 535 permanent-mold injection castings. But now, for the radials, it’s different. They, too, were originally made from castings, but after buying the company, we discovered the patterns had gone through a fire. They weren’t destroyed, but because of the heat, they were distorted. I didn’t want to pay a fortune to have new ones made, so we took a good casting and reverse engineered it. We now make the whole thing out of a solid 2024 aluminum billet,” he reveals.

“It takes two operations on the lathe and three on the mill, the longest being a 4th-axis op that takes about four hours. It’s 4th-axis indexing, but it’s also 3-D contouring on each surface. The finished appearance is great, and that’s important,” say Massa. “I have the little radial parts anodized so they look nice and sexy once they’re put together. When items like this are made well and look good, you’ve really got a winner.

“If a VF-4SS is free, I can put the billet in, walk away, come back four hours later and there’s a crankcase. But when I need the machine for different work, I can just interrupt things. I don’t have to tear down the engine setup; I can leave it on the end of the table and do something else. I can work on two things at once, so to speak – a few hours here, a few hours there.”

Without this flexibility, long combined operations like the three required for the radial crankcase could cause a real bottleneck in Southern Cross’s shop operations. “This way, the engine doesn’t steal all the machine time,” notes Massa. “It lets us work around it.

“I’m always careful to not let my engine company step on my machine shop’s toes. It’s get it in, get it done and get it out.” But that aggressive production is tempered with an important caveat: These engines have to be well made. After all, some guy might buy one, strap it on his back and go jump off Mount Robson.

“We can’t just bang ’em out,” stresses Massa. “They’re going to fly; they’ve got to be bulletproof.” And while crankcases don’t have to be extremely accurate, – holding half a thou’ is no problem – things like bearing bores do. So Massa has to trust his machines to deliver the quality he needs, every time he needs it, but without stealing too much of his shop resources.

“My engines remain a separate company from my machine shop,” says Massa, “but I depend on the shop to machine them.” So, a precision-obsessed job shop is tasked with turning out his consumer-oriented products. Massa can’t sell those products at anything near commercial aerospace prices, so how does he make it work?

“There’s no need to reinvent the wheel,” declares Massa, “but smart shop management is what’s demanded here. A big part of that is having the right machines, and matching the right machine to the job.”

An old adage warns: When the only tool you have is a hammer, everything starts to look like a nail. We all tend to make-do with what we have, often without realizing the paradox of problems that doing so can cause. “There’s definitely no need for that,” concludes Massa. “It’s the CNC age, mate. We’re much smarter now.”

I chose the VF-4SS Super Speeds because they give me so much table length and high-speed cutting capability for the price. We have a lot of fixtures and stuff set up to go straight on the Haas, and we like to leave those machines configured for 4th axis work. It saves a lot of time to have the rotary always mounted on the end of the table – its quick to set up, and away we go. Some customers have recurring requirements that we can re-fixture and machine with a minimum of effort this way. What I’m saying is, the VF-4SS is big enough to put lots of stuff on it.