Small Wheels, Big Progress - Brompton Bicycles

Thirty years ago, a young engineer and cyclist named Andrew Ritchie designed and built a prototype folding bicycle in the back bedroom of his home overlooking the Brompton Oratory in London. Little did Ritchie know at the time, but 30 years on he’d be running Brompton Bicycle Ltd, and overseeing production of 14,000 folding bikes a year: a £5 million turnover business.

For those who have never seen one of the company’s small-wheeled marvels, the Brompton bicycle is one of those brilliantly conceived and unrivalled step changes in engineering design that comes along once in a blue moon.

When the three frame parts are folded, it’s no bigger than a small suitcase and can weigh as little as 9 kg. It unfolds in 10 seconds, clicking into place with a rigid precision that reveals why Brompton offers a five-year warranty on its machines – all of which are still built in the UK, at its Brentford factory.

“We are the last quantity bike manufacturer in the country,” says company project manager, William Butler-Adams. “In the past five years, our sector has grown by 15 percent.”

Much of this growth is undoubtedly due to the general increase in bike sales. Part of it is almost certainly due to growing costs and restrictions for motorists, especially in congested areas such as South East England and central London. Prompted by the rail companies, many Brompton users carry their bicycles on the trains – assembling them at the station to complete the last part of their daily commutes.

In years gone by, the bike was the reserve of the die-hard Brompton enthusiast – a slightly eccentric, often besuited figure derided by mainstream peddlers. These days, more and more frustrated commuters are seeing the light.

“For a long time, the bike wasn’t well understood by the cycling fraternity,” admits Butler-Adams. “Hinges can lead to difficulties regarding front and rear wheel alignment, rigidity, safety and responsiveness,” he says. “The accurate machining of these hinges is crucial to avoid rock and movement. The cynics considered hinged bikes a flawed concept

An unfortunate state-of-affairs for the company – one that did little justice for what has ultimately proved itself to be an inspired innovation.

“A bike hinge may sound like a simple component,” states Butler-Adams, “but on our latest revised hinge we are using cutting-edge technology, such as 3D CAD modelling, rapid prototyping with resins and a state-of- the-art CNC machining centre. All of this means that we can produce components to very tight tolerances, giving us increased quality and longer product life.”

The new Brompton hinge is the biggest change on the bike for 15 years, and technically one of the most challenging ever. As part of its development phase, Brompton spoke to a number of possible machine tool suppliers. According to Ritchie, it was the positive attitude of Norwich- and Leicester-based Haas Automation UK (sole UK distributor of the U.S.-built machine tools) and their enthusiasm for the project that prompted Brompton to place an order for a Haas VF-1 40-taper vertical machining centre.

“We’d heard very good things about the standard of engineering on the Haas,” says Ritchie, “plus we spoke to another company that was using a Haas machining centre and they gave us the thumbs-up. Of course, price was also a factor. All in, the VF-1 was exactly what we were looking for.”

Before the arrival of the Haas, all of Brompton’s hinges were manufactured on a machine tool designed and built inhouse by Ritchie himself.

“The bespoke machine is fairly inflexible,” he says. “So it was time to replace it. However, the problem wasn’t finding a machine to do the job, it was finding a solution to the technical aspects of the project, such as the workholding, methodology and the ergonomics. It seemed there were a million ways of making the components, and we needed someone to help us find the most efficient and cost-effective. We had enough to worry about with engineering the bike, so it was time to call in machine tool professionals.”

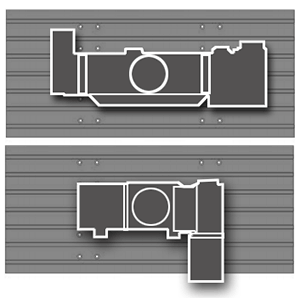

Realising they were going to have to work hard to reach Ritchie’s standards and expectations, Haas UK set about designing a method for clamping the cast-iron hinge, including a solution that would be able to compensate for the irregularities of the cast faces.

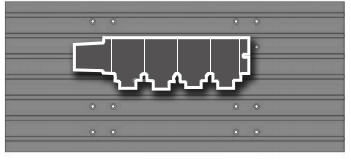

The solution is based on a Haas QuikCube multi-fixture system, where a hinge casting is loaded using an innovative locating/aligning mechanism. This is repeated four times – on the four faces of the cube – and the whole QuikCube is loaded on the VF-1. The rotary table and right-angle heads on the VF-1 mean that the hinges are completed in a single setup – four at a time – something that Brompton was never able to achieve previously. Tolerances are ± 0.05 mm on critical dimensions.

“While this project was originally conceived to improve the fatigue life of the hinge, the Haas VF-1 gives us so much more,” says Butler-Adams. “It improves our efficiency, reduces our cost base and increases our productivity by 20 percent with the same workforce. We now have enough capacity to tackle important new markets. It also provides better accuracy than we ever hoped for, and we now have total flexibility to make different types of hinges. In fact, when it comes to versatility, it’s brilliant,” he enthuses. “We simply pick up a different cube, load the parts, press the Cycle Start button and away we go.”

And it seemed that the engineering department at Haas UK’s Leicester Technical Centre – like the machine itself – exceeded Brompton’s expectations.

“The project support from Haas UK was superb,” says Butler-Adams. “I think many suppliers would have walked away when they saw what we were asking, but Haas kept working at the problem until we had what we wanted; it really made all the difference. We developed a good relationship and we got through to the end.”

According to Butler-Adams, the operator has found programming the Haas as easy as, well . . . riding a bike. Quoting the training operation as a “real success,” the operator is regularly shaving time from machining cycles. Important time savings, when you consider that working flat-out, the Haas VF-1 will process 45,000 hinges a year with plenty of capacity for more. However, Brompton is the first to admit they are not in the “volume” market.

“My aim is not to pick up production and move it to Asia, especially with high-technology components such as the hinge, which make the Brompton what it is,” says Butler-Adams. “We don’t and can’t operate in the £300 bike market – that’s not where we are. We make high-quality bikes that are capable of thousands of miles and last for years. Our standards are very high, and our customers are people who have done their research and realise they are buying the best. Most of our components are bespoke, such as the brakes and the gears.”

Incredibly, even the tread on the tyres is a Brompton design.

“In terms of the VF-1, if we as a company are not prepared to invest in the sort of technology that makes us more efficient and improves our products, then the competition will have us for breakfast!” exclaims Butler-Adams. “The machine has been a revelation. We couldn’t have taken the new hinge into production without it and the support from Haas UK.”

As for Ritchie, with the air of a vindicated man he concludes: “I always thought it was a good idea to have a bike you could carry around with you.”

For all the cynics out there: a salutary lesson in patience, perseverance and engineering creativity.

I think many suppliers would have walked away when they saw what we were asking, but Haas kept working at the problem until we had what we wanted; it really made all the difference. We developed a good relationship and we got through to the end.

William Butler-Adams, Company Project Manager